Handling Fear

Stress and fear are essential to survival. They are part of the set of responses that humans have evolved to react appropriately to stimuli that might represent a threat to life. The stimuli can be visual, aural or olfactory – the sight, sound or smell of potential danger can all trigger stress and fear. The evolutionary reward for effective reaction is obvious: survival and with it the opportunity to reproduce, without which extinction would quickly follow. At an appropriate level fear provides benefits in a violent situation; but if the fear becomes too extreme it can actively harm our chances of survival.

The reaction to fear is popularly called the “fight-or-flight response” or more formally the “acute stress response.” Calling it “fight or flight” is, however, somewhat misleading as there are a

number of other reactions that are possible. These include freezing in place unable to act. This is a common reaction to stress in some prey animals (think of the “rabbit in the headlights”

behaviour) and is believed to have evolved because remaining motionless may lead to the potential victim not being noticed by the predator. Many predators have eye sight that is acutely sensitive to

movement and will overlook a stationary object. Another common reaction to fear is goose bumps. It has been speculated that this is a reaction designed to “puff up” the animal to look bigger, and

therefore a bigger risk to the predator. It is no longer effective with humans as we have lost the long body hair or feathers necessary to create the illusion of greater size.

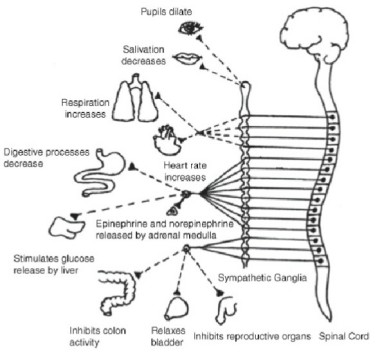

Regardless of whether the reaction to stress and fear is fight, flight or freeze, it has to happen quickly in order to be effective. Sitting and pondering danger is a good way to end up as the next meal of a hunger predator. Fear, and the chemical responses it triggers, are not governed by the logical “higher” brain. Instead it is the more primitive emotional system which responds quickly. At the heart of this primitive system is the amygdala - two almond-shaped nuclei located deep in the temporal lobes of the brain. It has the primary role in the processing of memory, instinctive decision-making, and emotional reactions. When danger is sensed the amygdala triggers the immediate release of certain hormones (for example, epinephrine, norepinephrine) that act within the body to prepare the person to respond to the fear. Once the danger is passed, the amygdala ensures that the reaction that resulted in a successful avoidance of death is written into the memory ready to be instantly accessed and reused next time. As an aside, this can have unfortunate consequences when the stimuli appears to be identical triggering the same response. There are many cases of people running into danger because their amygdala has programmed them to think that the location is a place of safety. For example, running towards a fire to get to the building exit instead of towards the fire escape is not unheard of.

What are the effects caused by the hormone release? During stressful situations there are mental (cognitive) and physical (somatic) effects. The extent to which these are experienced depends on a number of factors which will be discussed later. Fear is the first and most obvious mental effect of stress, triggered by the release of hormones. This is immediately followed by a whole range of further effects which may include:

- Increased aggression

- Mental anxiety

- An inability to concentrate or think rationally

- “Fat fingers” – the inability to perform learned techniques particularly where they require fine motor skills

- Extreme nervousness

- A racing pulse

- Tunnel vision

- Uncontrollable shaking

- Behavioural changes occur to raise vigilance to help identify and appraise threats

As well as these noticeable effects, other physical changes are happening including:

- Increasing blood pressure

- Rising blood glucose levels

- Suspension of digestive and reproductive processes

- Reduction in inflammation

- Blunting of pain perception

- Ramping up of the immune response to promote defence

- Activation of processes to prevent overshoot of the immune response and the possibility of autoimmune damage

- Central nervous system activation via neurotransmitter, neuropeptide and hormonal messengers to enhance learning and memory processes

- Skeletal muscle blood vessels dilate; glycogen to glucose conversion accelerates to better fuel muscles, vasoconstriction of digestive and reproductive organ blood vessels occurs.

Together these changes selectively increase blood flow and oxygen and glucose availability to brain tissues and skeletal muscles that require energy to prepare for action.

The purpose of these mental and physical effects is to enhance the chances of survival in a dangerous situation. The physical effects are focused on mobilising energy resources for instant use while simultaneously inhibiting body functions that are non-essential for immediate survival. The mental effects are focused on narrowing concentration to the threat itself eliminating superfluous detail. It is important to note that the extent to which the effects are experienced varies by individual and, in particular, the frequency of their exposure to the scenario. When a scenario feels wholly familiar there is often less or even no stress and without the stress there is no reaction. This is an important point – there needs to be a balance: enough stress to provide the benefits of the reactions, but not so much stress that the negative effects overwhelm the positive.

It can be seen that these reactions make complete sense when dealing with a physical threat from, for example, a wild animal. Focusing everything on running away across the open savannah, or striking

out with maximum power against the closest predator are likely the best survival strategies. The animal faces these threats every day of its life and its reaction is highly tuned. The strategies make

much less sense in the complex jungle that humans inhabit and the infrequency with which we experience the fear and flood of physical and mental effects means we are often incapacitated by fear

rather than empowered. Training and experience is critical if we are to utilise the benefits of stress and avoid the downsides.

How then can stress and the associated reactions help us in a self-defence situation? When stress exists at a low level (such as that experienced by a competitive athlete who is confident of their

ability) performance increases. Generally this low level of manageable stress causes performance of simple skills to increase as the increased aggression, increased uptake of oxygen, increased blood

sugar level and greater muscular tension provides an “edge” to performance. “Simple skills” in this context means simple relative to the ability of the individual – so skills and techniques that the

person can perform without thought. For example, in a martial arts competition or grading a straightforward punch or kick will be delivered with more power, speed and accuracy. Low level stress

does not provide all round benefits to performance though. While simple skills can be improved, techniques that are complex or difficult for the individual, or require very fine control, will degrade

as stress is not conducive to conscious control of the body. That's why it is so important to go into competitive situations fully confident and not to try something "clever" if you aren't certain if

it'll come off - the stress will almost certainly ensure it'll go wrong.

Reaction times are also much better in low stress situations. We have all experienced the difference between normal reactions and this apparent super human reaction speed in moments of sudden stress.

Ask someone to drop a small object near you, chances are you won’t get anywhere near catching it. Knock something valuable off a table and our hand snaps down to catch it before it has fallen more

than an inch or two. Try and catch a ball to win £1,000. You’ll probably fumble and miss as the logical brain responds to the stress and scrambles your reactions. But when a child accidentally kicks

a ball towards you somehow you’ll “sense” it happening and unthinkingly throw up a hand to deflect it, usually flawlessly.

The reason for the difference in speed is the engagement of a different part of the brain along with a lack of indecision – you act without thinking. All mammals including humans manage the super

human speed by bypassing the slow pathways of conscious thought, or the higher brain. As well as the effects discussed earlier, these hormones allow us to bypass the constraints the higher brain

normally places to prevent damage to the body (e.g., by moving too fast and tearing a muscle). This is the fundamental difference. Preparing to catch a falling object to test your reaction speed does

not create stress: no stress equals slow reactions via the conscious brain. The valuable object, like your phone, hurtling to destruction creates instant stress and lightning fast reactions. But the

really valuable object – that Ming vase – creates massive levels of stress and then the fumble fingers set in.

However, self-defence is not a competition and the positive benefits experienced by professional athletes are highly unlikely during violent encounters. Most people have never been exposed to real

violence and therefore stress levels are likely to be much higher. Instead of providing positive benefits, the physical and mental effects will combine and lead to a rapid reduction in the ability to

apply any learned skills or even any rational analysis to the situation. It is entirely possible that you'll abandon all attempts at self-defence and flail around or lie down getting punched. The

effects described earlier will begin to run out of control. The elevated pulse and elevated respiration can cause actual or perceived rapid fatigue and may induce panic as a feeling of

breathlessness sets in. If you aren't used to being exhausted this can increase the panic. As combat continues you may suffer from hyperventilation which causes respiratory alkalosis. This has

symptoms ranging from a feeling of dizziness to fainting or even a seizure. Tachycardia (the racing pulse) causes similar symptoms. Peripheral vision may be lost. This reduces your ability to assess

possible exit strategies and escape routes. You may not see a second attacker coming in from the side. People attempting to help may be unobserved and treated as additional attackers. The focus will

be almost entirely on the person standing right in front of you rather than a potentially higher threat nearby.

Further, increased aggression can lead you to continue to fight, often with a very primitive technique, rather than attempting to disengage even if (if you were thinking logically) it would be

obvious that you should stop or take the chance to run away. For example, the fight may continue against multiple armed attackers despite the high risk of serious injury or death. Or severe mental

anxiety may set in leading to the abandonment of an effective defensive technique and the adoption of victim behaviours that encourage the attack to continue. You might even continue to pound a

helpless opponent instead of running, turning legal self-defence into an illegal assault.

How then can we improve our chances of experiencing the good effects rather than the bad? Stress is a common factor in all competitive sport and therefore there has been significant investment into

research on effective coping strategies. These strategies are common to stressful situations – that is, they are not specific to sport but apply across all aspects of human life where stress

may occur. This means that they are fertile ground for finding useful strategies for facing self-defence situations.

Coping strategies fall into three groups: task-oriented, distraction-oriented and disengagement-oriented. Several studies have examined coping strategies and attempted to correlate them to sporting success. While there is some variation between sports (e.g., alpine skiing which involves a one-off solo activity of less than two minutes requires a different approach to coping than a five set championship tennis match) there is a fairly consistent correlation between successful athletes and how they manage stress. The most successful approaches are task oriented strategies. Athletes that use avoidance-oriented and distraction-oriented strategies are statistically more likely to be less successful. Examples of approaches within these unsuccessful strategies include resignation, venting and distancing. That is, resigning one’s self to losing, shouting with anger each time a shot is missed, or trying to “forget about” what went wrong are all characteristics of sporting failure. Intuitively they would also be clear markers of failure in self-defence too.

It seems that we should be looking at task oriented strategies and how they can help us prepare for violent encounters. Examples of approaches within this strategy are mental imaging and action focus. Both are used in competitive sport with success and should be adaptable to deal with preparing for violence.

Action focus coping is a mental focus on action rather than outcome. It involves concentrating on the performance of techniques rather than the desired outcome. For example, a boxer should concentrate on delivering their best techniques, not think about winning (or worry about losing). The danger with a focus on outcome is that if the desired outcome becomes in doubt panic can set in, the stress level rises, the hormones explode and performance disintegrates. In terms of combat, the training of the samurai constantly come back to this approach: prepare for death before entering combat, commit to battle without thought of survival. This doesn’t mean that they wanted to die, rather that they knew that worrying about death induces fear which lowers performance. This mind set is hard to construct in a self-defence scenario because it is usually unplanned and unexpected. However, we can train in the same way that athletes do to try and improve performance and lower the risk of the hormone rush overcoming us.

For athletes the inability to have an action focus begins from them lacking awareness of the movements that they use to perform their sport. This makes them vulnerable to breakdown under pressure as they begin to focus on outcome and are unable to consciously recognise why their technique is failing. To address this, coaches work on building self-awareness of body movement in the athlete. This is based on construction and stabilisation of the entire required movement chain and the connections between components rather than on separately perfecting individual elements. We can use the same approach to prepare for self-defence. We know that the hormone rush will prevent us performing complex actions or in creating ad hoc clever sequences of techniques. Therefore we should design and then train to conscious perfection a short sequence of techniques that is applicable to as many scenarios as possible. Then we should test it over and over again concentrating on perfect execution (i.e., placing the mind on execution, not the effect). Research also suggests that the sequence should be tested in other situations when the hormone rush is there. For example, if you are claustrophobic, squeeze into a tight space and perform your self-defence sequence.

Mental imaging is a coping strategy of visualising the stressful scenario, and playing out your planned response. This makes the scenario less stressful – reducing the risk of hormone overload – should it actually occur. In a self-defence context, this would involve visualising different variations of the scenario – jumped in a dark alley, grabbed in a corridor, etc. – and then playing out the pre-prepared response detailed above when action focus coping was discussed. Simulating the scenario physical will also help. For example, getting someone to act out the attacker in the dojo.

In summary there is no way to stop the effects of fear, and you wouldn’t want to as it would reduce your chance of survival. But you can train yourself to expect the feelings, to understand what is happening and to deal with the consequences. Expose yourself repeatedly to close analogues of combat. Join a martial arts club and don't shy away from testing your skills against the scariest person in the club. Pick the biggest, most skilled opponent no matter how terrifying they are. Immerse yourself in your fear because only through experiencing fear will you learn to deal with it when it really counts.